Brian McLaren - Humane Spirituality, looking back, looking around, looking forward - Soularize 2021

Brian McLaren shared at Solarize 2021. Our theme was Humane Spirituality and Brian contextualized it within his own life's journey.

Although this year we will not have any Keynote speakers, we felt it might be important for you to hear the spirit and ethos of a past Soularize presentation.

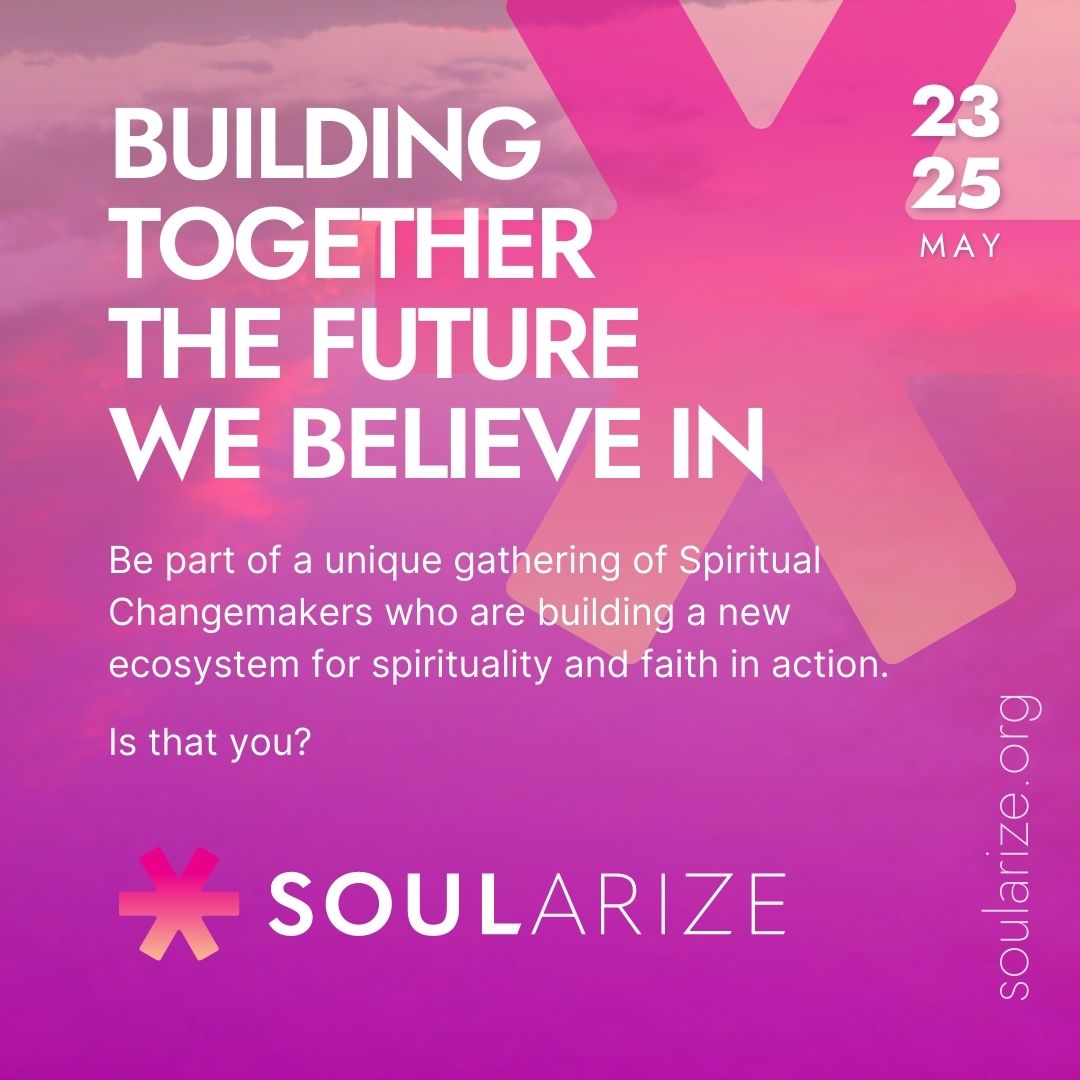

This year will be a completely different format. A truly hands on, three day facilitated experience. You can learn more by heading over to soularize.org.

Below is a rough transcription of Brian's talk.

__________________________________________________

Soularize 2021 - Brian McLearn - Humane Spirituality

My name is Brian McLaren. I'm really happy to be here with you all. And if we can put my slides up, that would be fantastic. I would like to just open our consideration of humane spirituality by doing a little bit of looking back, looking around and looking ahead a little bit about myself. I know it's hard to believe, but I grew up white. I grew up a white boy. And in New England, in an evangelical fundamentalist family full of love, full of deep spirituality and devotion within a context that I had no choice over. Its what I was born with. And I think it's important to remember everybody is born into some kind of context and every child grows up trying to make the best out of the context that we inherited in the 1950s to the 1970s, I watched my religious tradition go from being kind of marginal and on the edge to coming into the centers of power through the religious right. I was in trouble. I knew from a very young age I really liked science as a kid and I thought my mother would take me to the library and I would check out all the books on fossils and dinosaurs and animals and plants and birds. I just loved nature and I thought evolution made so much sense. It seemed to me to be beautiful. It seemed to me to have so much explanatory power. But I knew that in my church we weren't allowed to believe it.

And I remember sort of locking something away in my mind and thinking, okay, on some issues you just have to keep your opinions to yourself because the big folks at church won't really understand. I also had another strike against me, and because I was an English major and I loved literature, and one of the great things about literature is that it invites us to enter into the experiences of other people. And in a sense, we just shared in this kind of experience as Moksha sang for us in a different language that I'm going to guess very few, if any of us understand. And we were brought into musical forms that were different. And what literature did for me is it let me enter the experience of people whose lives were so different from my own. I remember years ago when I read the great novel by Chaim Potok. My name is Asher Lev, and I thought in those 3 or 400 pages I was brought into the experience of a boy growing up in New York City. I grew up in New York State, outside the city, but a boy in a hyper orthodox Jewish family who happened to have an artistic bent, and he realized that his art and his religious tradition were in tension. And I got to enter into his world through literature. But I also got a mirror to look back at my own world and my own experience when I was in graduate school.

I'll never forget the day I was encountered the word postmodern for the first time. I thought, That doesn't make sense. Modern means now, how can there be anything after the now? But it turns out in literature there was a whole movement that was called the Postmodern Movement. It was related to structuralism and deconstruction, words that are a lot more familiar these days. And I remember thinking, I hope this way of thinking never catches on in the real world because the Christian religion won't know how to deal with it. But of course, going to the 90s I had become a pastor. I had some very powerful spiritual experiences that sort of kept my feet on the path and I started realizing that that way of thinking I'd encountered in the 1970s was now on the street and people were coming into my congregation who were thinking in a different way and asking different kinds of questions. Meanwhile, the religious right had gained so much more power, and that power was amplified by megachurch pastors with television and radio and all the rest. And it felt that just as evangelical power was reaching its peak, there was some anxiety building, and the anxiety was that the younger generation wasn't buying it the same way that previous generations had. And for me as a pastor, it created deep. Discomfort because on the one hand I identified with the people who weren't buying it and who felt it wasn't working.

And yet, on the other hand, I felt there was still a treasure in the spirituality that I had inherited. And I felt starting in the late 80 seconds and early 90 seconds that I was peeling an onion. Maybe the problem is our music. It isn't peppy enough. Maybe the problem is our preaching style. It isn't relatable. Maybe the problem is our structure. Maybe the problem is our seminaries and training they're doing. And I kept peeling it back and I wondered if at the end there would be nothing left. As you peel an onion, all that's left is tears. But along the way, because of that little word, postmodern, an idea and insight hit me. And that insight was that what I had inherited was a modern form of Christianity. And there might be ways for me to be a Christian that weren't the modern form. Maybe my problem wasn't with the essence or heart or spirit of my inherited faith. Maybe my problem was with a modern form of it, and that gave me enormous permission and freedom to explore pre-modern forms. That for me meant learning about some of the mystics and learning about some of the monastic movements and learning about some of the kind of what some people call the radical reformation Christians who actually believed in peacemaking rather than in justifying war and put all those together. And it felt like more space was opening up to imagine what we might call postmodern forms of Christianity.

And at some deep level, what I was looking for was a form of Christian life and spirituality that was more humane. Now, years later, I would end up in a whole series of relationships with people from many other traditions, Muslims who had gone through a similar search for a more humane form of Islamic spirituality. Jews who are going through deep struggle to find a more humane form of their own rich tradition that they felt was being in many ways corrupted by people who were using power to hurt other people, sick people of the sick faith, people of the Hindu faith, people, Buddhists who each in their own way were looking for forms of their faith that were more humane. Many of you perhaps have read Thich Nhat Hanh, who looked at his own Buddhist tradition and said, So many of us are seeking enlightenment for ourselves and we haven't learned how to bring our teaching to engage with the social injustices of our world. He was looking for more humane forms of his tradition. Uh, and so that was a journey that I was on all through the 1990s. That's when I wrote my first book at the very end of the 1990s, and along the way started meeting a few other people who were what you might call spiritual innovators. But then 9/11 hit. And when 9/11 hit, we saw this resurgence of fear and hate among the the white Christian majority in the United States. A new wave of Islamophobia as the nation seemed to descend into kind of a warrior trance where the religious right in its many different forms, weaponized even more.

I remember a few weeks after 9/11, it was December of 2001. A friend of mine had been invited to a meeting where a well known televangelist said to a group of Christian leaders from around the country, he said, It's now or never. It's us or them. And what this religious Christian leader was advocating was nuclear war with Islam. And I remember thinking, these are dangerous times. And and these leaders are fools. And if if people follow them, we're going to watch some of the ugly, very likely the ugliest things that have happened in human history. And you might think I'm exaggerating, but I bet a lot of you feel the same way. I feel like we've lived every year since 2001 on the bridge with our on the edge with our our toes hanging over a cliff. That if we don't learn a more humane spirituality, learn to live it and manifest it in the world in a contagious and winsome way. There are a whole lot of other people who are using harmful forms of religion that feel to them devotional and good and warm and and things that bring them together with others on some deep way. But it's it's always bringing benefit for an in-group at the expense of an out-group. And so we I found myself in the early 2000s bumping into people like Spencer Burke and the Solarized community and many others who are springing up with their own frustrations and their own story and their own journey.

Just as in a sense, we were entering a decade of what many have called, especially my friend Diana Butler. Bass is called a great religious recession. We all know about economic recessions, but there was a religious recession as the Roman Catholic Church faced. They certainly did everything they could not to face it. It was courageous journalists who brought who brought courageous whistleblowers and and victims to come out of the shadows and tell the truth about pedophilia scandals. And, of course, the struggle in the Catholic Church is continued even more as mass graves are being dug up in Catholic boarding schools. And it wasn't just Catholic. It was also Protestant schools, too, and all kinds of evangelical televangelist scandals. And it just felt like religion was self-destructing before our eyes as it was gaining political power. It was losing its moral, its moral ethos and looked like a caricature rather than an inspiration. And many of you will be familiar with the conversation that emerged Solarized played such a huge part of it with what was kind of new in those days, an online platform called The Ooze, and it seemed like many people had grown up as I did. Evangelical. Many people who had grown up mainline Protestant, many people who had grown up Roman Catholic and other forms of Christianity were making a choice.

Many became what now is called sbnr spiritual, but not religious, where they tried to maintain some sort of spirituality, but they were disaffected with all of the structures and external institutions of their inherited faith. Others became secular and became hurt because they'd been hurt, traumatized, damaged, harmed by very harmful aspects of religion. Many became atheists and agnostics. And really the word spiritual was a polluted word, as was the word religion. And many stayed and tried to make the best of it. And meanwhile, I think about the enormous effect of Solarize in those early years. I remember when Spencer, I first heard the term a learning party and I thought, what a beautiful phrase, because we learn things when we're relaxed and having fun and in a spirit of openness and even play that we don't learn when we're under threat and when we're under tension. I remember just this sense of showing up at events where the most important thing wasn't necessarily what was happening at the front, but it was all the people who were meeting each other and building relationships. Some of the most important relationships of my life happened at some of the early solarize events through the wonderful networking work of Spencer and all the others involved. A lot of folks don't know this, but in that emerging conversation where we had white evangelicals and white and Roman Catholics being brought together with mainline Protestants, Spencer was one of the very first people to invite people from the LGBTQ community to be presenters, not to talk about LGBTQ issues only, but just to talk about life and faith and and to just in a sense, be part of the community and leaders in the community.

Spencer was one of the first to break across the Catholic Protestant divide and invite Catholic leaders. I met Richard Rohr, who's now a dear friend and colleague at a Solarize event with Richard. With Spencer's great help. Not only that, but Spencer is one of the first to say if this conversation is really going to go anywhere, Christians need to learn how to have the conversation with people of other faiths and not just behind their backs, but in the room. There was an event in Seattle where Spencer not only did a beautiful protocol where he acknowledged the land on which the we were having this event, which by the way, here would be the land of the Juaneno and other first indigenous peoples of California. But to actually invite some elders from the local Native American communities to come and lead a potlatch at this event and brought us into space that many of us had never been before. And to listen and learn respectfully. A gathering shortly after September 11th, that same gathering, Muslim students were invited to be sure that their voice was heard when this rising tide of Islamophobia was just was just beginning and so much more we could say about how important what happened about 20 years ago was to setting the stage for a new conversation about a humane spirituality.

I'll just mention one other thing that involves Spencer. Quickly, Spencer wrote a book with the word heretic in the title. And the word heretic is a word with a history in the Christian faith that literally has a death toll. When people were identified as heretics, it meant that they could be subject to arrest, inquisition, imprisonment, torture and death. And and what many of us have had to realize is that when there is an inhumane form of spirituality, when there is a kind of religion that has been weaponized to hurt people. You have to be willing to take great risks. And you have to be willing to have the word heretic applied to you if you're going to stand for the lives of your neighbors. And so it seems to me that so much happened in the years just after 2000, 2001, with so many important spiritual innovators here in the United States and around the world coming together. I remember one of the big insights that hit me in those years was the realization that modern Christianity wasn't just a doctrinal or dogmatic construct. It was also a racial, social, political and economic construct. Years later from a Native American named Mark Charles, I began to learn about something called the Doctrine of Discovery. And if we had a lot more time, it's something I'd love to explain to you all now.

But if you're like me for most of my life and you've never even heard that term, let me just encourage you, it's easy to Google doctrine of discovery, and we all remember the little poem. In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue. What we need to learn is that in 1452. Pope Nicholas sent the kings of Europe out with a horrific and inhumane mission to pursue. And that mission literally, if you read the documents of the 1450s. The leader of the Christian religion. In the West said to the kings of Europe, go into all the world and make slaves of all the nations. If those words sound familiar, they it's like it's stunning, the parody of the original words of Jesus. Make slaves, take people's wealth, take their nations and do it all in the name of Jesus and the one true church. And sadly, some decades later, when the Protestant church broke away, in a sense, they kept the doctrine of discovery. They just called it things like Manifest Destiny. Or if you hear the term American exceptionalism, you understand we're an exception from the rules of normal morality. Anything we do is justified by God. And it has this same inhumane ring to it if we hear it in its historical context. And then I realized that the Christianity I had inherited with my parents didn't know this. My grandparents didn't know that, But they had been inducted into a form of spirituality that had been framed and reframed by the doctrine of discovery.

So that Christian supremacy became a cover for white supremacy. And the Christian religion became the chaplain to a capitalist enterprise that created a global economy based on two things. Extraction of natural resources. You could let me give you another way to say that. Extraction of the long term health of the planet for the short term wealth of the exploiters. And second, along with extraction from the earth, was the exploitation of labor. And so you put those two together and suddenly the discomfort that I had been feeling in my own spiritual life helped me realize that this way of looking at the world is inherently inhumane. And the fact that I was dissatisfied didn't mean there was something wrong with me. It meant my eye was sensitive to the inhumane ness of what was going on. And I'm going to guess that. All of you have probably felt a same kind of tension. You couldn't identify it at first, but you knew you were being called to something more humane. Bye. You know how decades don't always work out exactly right to describe things. So, for example, in some ways, the new century probably really began on September 11th, 2001. I think that first century kind of ended with Obama being elected. And when President Obama was elected here in the United States, none of us realized how the white lash that would follow the resurgence of white supremacy under the guise of the Tea Party would eventually lead to Donald Trump.

And similarly, the struggles that were going on in the Christian community here in the United States, especially the white Christian community here, none of us could have guessed that there would be a kind of backlash against the voices of liberation theologians and the voices of black theology and the voices of feminist and queer and and ecological spirituality and the emerging conversation that many of us were part of. We never realized that the backlash against those proposals and breakthroughs would lead to people like the ones whose names have been in the headlines recently, from Jerry Falwell Junior to Franklin Graham to any number of other people. But in a sense, what we've watched happen is our many of our religious communities doing one of two things, either deciding to side with the voices that are calling for a return to the supremacies of the past, or they've been silent because they're afraid to speak because their major donors watch Fox News 24 hours a day and the Fox News of Rupert Murdoch matters more to people than the good news of Jesus Christ. Even one of the most remarkable things of this last decade has been how Pope Francis has spoken out to think the leader of the Catholic Church has spoken out about the need to hear the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor. Talk about an advocate for humane spirituality.

Of course, he hasn't gone as far as many of us would wish, but just the fact that the leader of the largest Christian organization in the world, the largest single religious institution in the world, has spoken out in these ways. It's remarkable. But guess what? There's a whole lot of people in the Catholic Church who would be very happy to see Pope Francis gone even more so after some things he said just last week. So you see there are these movements forward toward a more humane spirituality and then there is a backlash, often a violent backlash. And we've seen it even in this these last couple of years with COVID 19 and with the last election leading to January 6th. And many of us are concerned that January 6th wasn't the culmination of a bad idea. It was just the first wave of a long term coup attempt to try to bring power back to people like me, old white people from a Christian background who are nostalgic for a way when they could make money easier and they could exercise their power more easily. So we see now a backlash against science, a backlash against democracy. And we're and a backlash against the very idea of truth. And so here we are at this moment, a group of people seeking to have not only conversation but action inspired by a more humane spirituality. And one of the encouraging signs that I see when I not only look back, but look around at this moment is a kind of convergence that really would have been unimaginable to me 20 years ago.

Just to share a personal experience, I was invited to be part of something over the last decade called the Auburn Senior Fellows and an Auburn seminary brought together religious leaders, Jewish, Buddhist, Muslim, Sikh and others, and a number of different Christian leaders and said, We'd just like to bring you together. We want to help you become friends. We want to help break down some of the silos. We want to help you bring bring in a sense, benefits and gifts from one another's traditions and bring to our nation and our world a place where religious leaders from different traditions are simply trying to know and understand each other to work together for the common good. It's been an incredible experience in my life to be invited into deep conversations where we all find out how in each tradition there are the same kinds of battles going on. Our battles toward a more struggles, toward a more humane spirituality, or to pull us back to old patterns of the past. And so what's so amazing and what this I just I don't think I can communicate how surprising this is. Just I'll tell you a quick story. Pope Francis came out some years ago with something called Laudato Si, a call to the people of the Earth. This was not a letter to Catholics. It was a letter to all people to say, let's hear the cries of the earth and the cries of the poor.

And there were a group of us who were not Catholic, who were were contacted by a number of people who said, listen, you need to understand that many of the bishops of the Catholic Church will go against Pope Francis's invitation. And they said we need people from outside the Catholic Church to echo the call from Pope Francis. So I was honored to be the organizer for a response in Washington, D.C., at the National Cathedral, where we brought together a wide, multi-faith group of people who said, you know, I'm Muslim, but I think Pope Francis is right and I stand with him. And here's what we Muslims are going to do about the call. I'm Jewish. I think Pope Francis is right. Here's what we Jews are going to do. I'm sick. Here's my background. I agree. And a whole range of people came together. And when the event was over, one of the Muslim scholars and diplomats, political leaders who was part of this called me. And he said, Brian, I just want to tell you what a great experience it was to be part of that event. And then he started telling me his own story in the Islamic world. He's a Sunni Muslim and in the Sunni Muslim world, he's been involved in what we might call a struggle for humane spirituality. And as he shared his struggle, he said to me, I'm so glad I got to meet you, because I didn't know that people in the Christian community were having similar conversations and similar struggles.

And oh my goodness, over the years you start finding people across Christian denominations and then across other faith traditions too, who all seem to be drawn to some kind of humane spirituality. And a characteristic of it is that it's looking for allies wherever they could be. And this sense that whatever is going to get us out of the mess we're in is going to require deep, multi-faith collaboration. So when I look around today at this moment, I need to be honest. And I think you feel the same way. We we are at a time of institutional polarization, paralysis and weakness. There are a lot of ways to understand it. One way that I think has a lot of merit is that we're finding out that the world is not run by governments. The world is run by oligarchs, powerful people and corporations that have been, in a sense, buying governments for decades. And guess what? They've been buying religious leaders as well through the whole donation system so that religious leaders become afraid to speak out at what their donors don't want to hear. And so we are at a situation where we need our institutions to work as never before to help us engage with the crises we face. A global ecological catastrophe that arguably human beings haven't faced since we became a species 200,000 years ago.

Uh.

I mean, what is ahead for our children and grandchildren? I'm sure you're aware of this is. Is breathtaking. Not only that, but we're in a moment when the inequality between a hyper rich, super elite minority and the vast majority of human beings, that gap is so great. And it's not only an economic gap, but that gap in money creates a gap in power so that very few people have power to get away with murder. And not just murder literally, but mass murder, because the effects of being owned by corporations are it's leading to places that all of us have the ability to imagine. And when you have that kind of instability. And when those leaders, those elites know how to set people against one another to to inflame racial tension, to inflame political tension, to inflame regional tension, to to inflame international tension. Then you realize that every division in human society could be weaponized at any moment. And right when we need to come together the most, there are people who are happy to divide us the most. I wrote a book in 2008 that was called Everything Must Change, and it was about global crises. And I was traveling around the world talking about the book. And I want to protect privacies for reasons you'll understand. But I was in another country. And the my host came to me and said, There's someone who'd like to meet you. He's an advisor to the president of this country and we think you should meet with them.

So arranged a meeting and this fellow sat with me. And this couple's home and said, the president read your book and bought copies for all of the cabinet. And he said, we've had discussions about the global crisis you talked about. And I'm here with a message from our president, especially about climate change, because this president was one of the leaders in the world dealing with climate change. And here's the message. We're witnessing the failure of the nation state to face our most pressing problem. He said, the president wants you to know he's in the inner circles of these discussions. And he just said, do not expect them to solve this problem. They're incapable. The institutions are too weak. The people are too divided. And. And so here we are at this moment. And everything that we saw that that I saw back in 2009 and that conversation has just continued to unfold. And it's not just our political leaders. So many of our religious leaders are stuck in irons, as they say in sailing. They they don't know how to get momentum to move forward. And so it's clear that the center isn't holding and that our institutions, religious and and secular, are captive to donors and stuck that in many ways the emperors have no clothes except in their own minds. And here's the thing. Nobody is coming to fix things. Nobody is coming to fix things.

If you think that we can win an election and have people come to fix things. I wish you were right. I don't think you're right. If you thought some academic could come up with a theory that would fix everything. I don't think that's right. I think that we are having to come to the conclusion that we are the ones that we've been waiting for and that if there is power for the kind of change that we need going forward for humane spirituality, it's going to have to happen through the power of mass and social mass social movements. And I'd like to take a few moments, my last few moments talking with you a little bit about mass social movements. Now, there's a lot of different ways to describe movements, but one is to talk about three different kinds of movements. When I wrote this book that I mentioned, Everything Must Change. I remember at the end of the book I didn't have this language, but here's what I saw. First, we have a lot of movements that focus on personal and in-group well-being. Movements that say the world's a mess and the only way we can make the world better is by changing one human heart at a time. And so these would be movements that that create subcultures of well being. And the idea is, look, if we don't have subcultures of well being, we won't ever be able to get to a better place.

Let's invest in the development of subcultures of well being. And so the explosion of yoga around the world is a great example of this. One of the most effective movements in the West in recent decades of bringing people together and say, on your mat you can learn to have well being while the rest of the world is falling apart around you. And we as a community begin to manifest a different spirit, a different way of life. And these movements are so important. Many movements in the Christian faith would be part of this. This idea personal in-group, individual transformation to create subcultures of well-being. You know, I'm old enough. I grew up sort of in the hippie era and the desire to go out and form a commune out in the out in the wilderness somewhere or an urban commune is this expression, can we create a subculture of well being? That's first kind of movement. And I think it's super, super important. Second kind of movement would be an institutional challenge and change movement. This is a movement that says the institutions are harming us, the institutions are failing us. We don't want to destroy them. We want to change them. So the civil rights movement is a fantastic example. They built mass social power to the point where finally Lyndon Johnson and the Congress had to come together and pass civil rights legislation and we solved all of our civil rights problems.

No, that's not true. We didn't solve the problems. But if we hadn't had the legislation, imagine where we'd be now. My dad is an interesting example. My parents were two of the most racially loving people that you could ever imagine. Especially my parents were born in the 1920s when my mother died and I was going through her papers. I found a paper that she wrote when she was in high school about race. And it was the kind of paper that probably would be illegal in many schools today who are outlawing you, being able to talk critically about race. And this was when she was 16 or 17 years old in high school. And so my parents were wonderful examples. But my father's father was a white supremacist. He was a theologically justified white supremacist. He had Bible verses. He was an American. He was born in Scotland, but he was a white supremacist. And and I when my dad was very old before he died, we were taking a walk one day. And I said, Dad, how did you become so different from your dad? How did you develop such a better understanding of race than your dad? And you might think that he would have said the church or some Christian organization. He said the US Army. A legislation. That that integrated the Army in World War Two. Uh, made it possible for my dad to work side by side with people of other races.

And it was the experience of being thrust together that changed my dad. And so legislation is super important. It's not the whole solution, but it saves lives. It is a really important solution. And I'll just tell you, if we're if we're going to do anything about climate change, it's very hard to imagine surviving without legislation. And so we have organizations that focus on institutional challenge and change. And then we have a third category that you might call radical alternative design and radical alternative design says. That tends to be critical of the first two groups. You can have everybody you know, you can try to get a lot of people having personal well-being, but the system's going down. It's inherently, inherently destructive. And if you care about the most vulnerable, for you to go to church and feel close to God is a betrayal of your neighbors who are barely surviving. And so it says we've got to give up hope on the existing system and we've got to try to create alternatives. And now some people do this in a specific area. They say the educational system is inherently unreformable. We have to create alternative forms of education. The economic system is unreformable. So we have to use democratic means to get rid of the current economic system or some would say some would say violent means would be justified, too, because sometimes in the radical alternative design community, some are violent, some are nonviolent, you would say, or people would say the the health care industry is inherently unreformable.

We've got to create some other approach to health care. And you know what? I'll tell you, when you study the complex of problems that we have, you find out, for example, there's a group of people who say the global economy is unreformable. We have to give up on that and create local living economies. And I'll tell you, when I listen to them and then I listen to the people trying to reform the global economy, here's what I find myself saying. If the global economy can be made more just, I hope it will. Because billions of people could die if it isn't. But if it all collapses, I hope that these folks looking at local living economies will be there to pick up the pieces because we'll really need them. And so I hope you feel what I'm suggesting, that we need each of these groups. We need each of these kinds of movements at this time to come together and say, how can we help individuals and small groups experience real well-being in these times? Second, how can we help organizations mobilize mass social power to bring change to existing institutions, governments, health care, industries, economy, economic industries, whole economies, businesses, corporations, and so on. And religious organizations too, by the way, because they're organizations that have people challenging them. And then third, how can we have people doing alternative design, imagining different ways of living entirely, creating today's counterpart of monasteries where people say, I want to be prepared if the system falls.

We want to have a group of people who are figuring out how to live and survive to survive post crisis. And so we look at these kind of groups alive and at work in our world. And here's something I can tell you. Very, very often if you're part of one group, you despise the other groups. Why do you despise the other groups? Because you know how important your work is and you wonder why those other people aren't joining you. You need their help and they're doing something different. And when you're tempted to despise them, it's understandable why you'd be disappointed in them. Why are you trying to reform a system that's unreformable? Why are you going off and creating a little commune in the forest when what we really need is to save lives and liberate people from oppression? And I've been able to see so many of these arguments at close range. And when I look ahead to the years ahead, the big question in my mind is how will these three different kinds of movements interrelate? Will they live in silos, in competition, or will they. Will they despise one another or will they learn to live in collaboration and coalition? The subcultures for Personal Well-Being. The Countercultures for institutional change and the neo cultures of radical experimentation.

And.

I believe that humane spirituality can play a role in all three. We need people who are developing a deep, humane spirituality in all three of these kinds of social movements to bring spiritual resources, spiritual insight to and to help these groups learn to not hate each other, but to appreciate each other. By seeing by doing the things that Spirit helps us do. Seeing things whole. Building character and resilience. Enhancing imagination and creativity. Promoting the common good and a bigger story. And relating compassionately and drawing inspiration from the spirit that is actually inspiring people in all of these different kinds of groups. And so what I would say we're in in the the stages of, of early stages of engaging in conversations like these is how a humane spirituality can help us at this time of great challenge and difficulty by telling a bigger story in which everyone and everything belongs, where my enemy is redeemable and where love is the Prime Directive. I'd like to. Just share a couple of quotes in closing and then we'll have some time for some some discussion. Fascinating 20th century intellectual Ivan Illich said neither revolution nor reformation can ultimately change a society. Rather, you must tell a powerful new tale. One so persuasive that it sweeps away the old myths and becomes the preferred story, one so inclusive that it gathers all the bits of our past and our present into a coherent whole one that even shine some light into the future so that we can take the next step. If you want to change a society, then you have to tell an alternative story. To me, this is part of the work of humane spirituality, of telling a different story. An economist friend of mine, David Korten, said the outcome will depend in large measure on the prevailing stories that shape our understanding.

Perhaps the most difficult aspect of this work is to change our stories. Thus, the true believers of the new Right gain power not by their numbers, which were relatively small, but by their ability to control the story. And as an economist, he recognized that Jesus was somebody who dedicated his life to changing the prevailing stories. And Salman Rushdie, someone who faced threats on his life by members of his own religion, said Those who do not have the power over the story that dominates their lives, the power to retell it, rethink it, deconstruct it, joke about it, change it as times change truly are powerless because they cannot think new thoughts. And so we live at this moment when our prevailing stories are failing us. They may have emerged to help us address problems in our past, but they are not yet addressing the crises that we currently face. And so each of us lives with an individual story as part of a group telling our group story that interacts with other groups with their own group stories. But we're looking for some larger story, some larger vision to help help us in a sense, find each other and come together. And there are many stories competing to dominate. But I think many of us believe that unless there is a spiritual story, a humane spirituality that can make space for us as individuals and our diverse stories that we don't have a new way forward. And so I'd like to invite her up again. And and as they play this next beautiful, beautiful song, I wonder if we could just sit looking back. Looking around and now especially looking ahead. And imagine a humane spirituality that invites us to rise together.